Dogs and their people: Companions in cancer research

Pets

Audio By Carbonatix

By Bob Holmes for Knowable Magazine, Stacker

Dogs and their people: Companions in cancer research

After a train carrying chemicals derailed and caught fire in East Palestine, Ohio, in 2023, residents were exposed to carcinogens such as vinyl chloride, acrolein and dioxin. Since tumors are typically slow to develop, it could take decades to know what that did to the locals’ cancer risk, but there may be a quicker route to an answer: The residents’ dogs were also exposed, and dogs develop cancer more quickly.

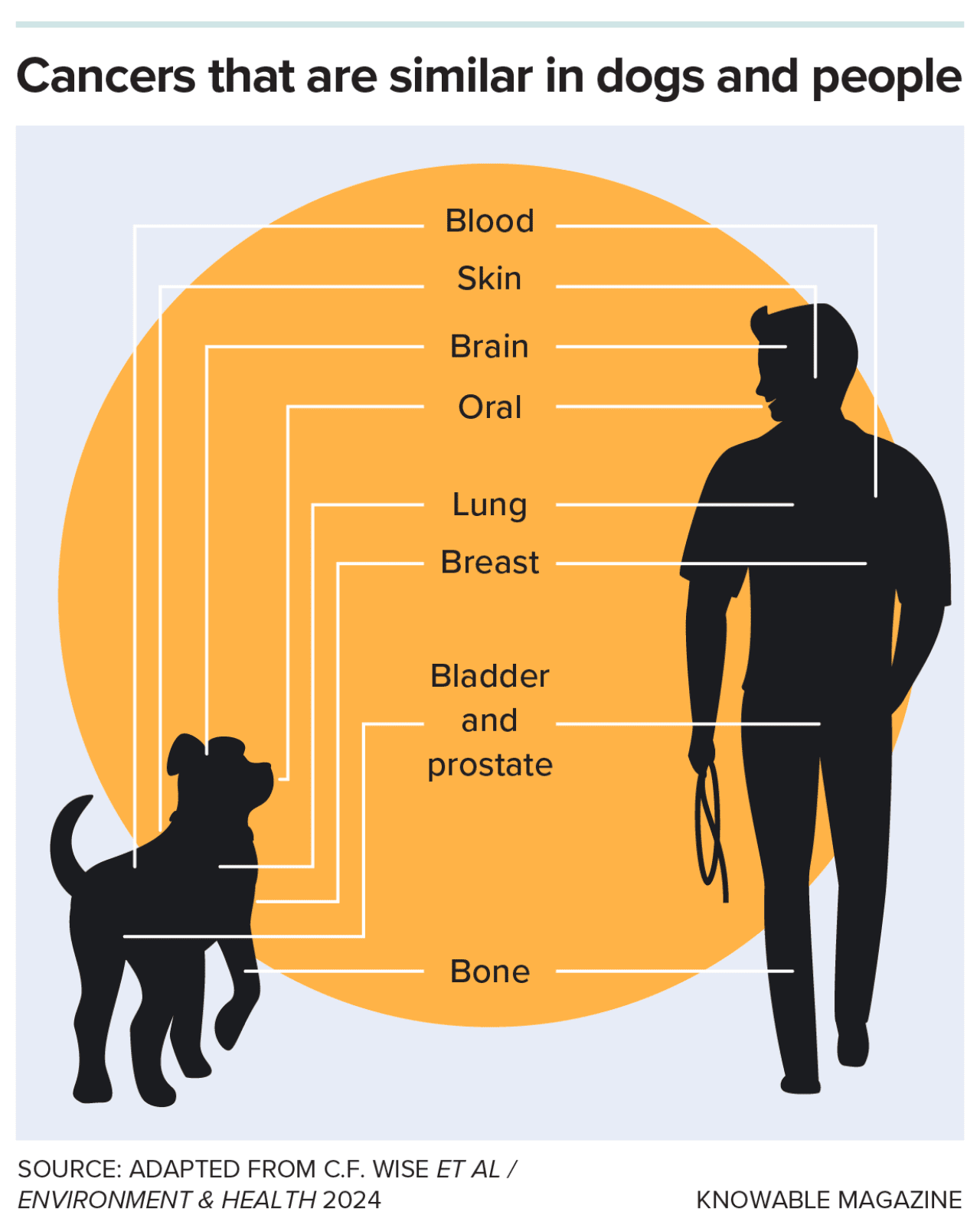

Studying dogs and their cancers turns out to be an excellent way to learn more about cancer in people. And it’s not just that dogs and owners share exposures to many of the same environmental carcinogens. Knowable Magazine reports researchers are also learning that cancers develop along remarkably similar pathways in the two species.

The faster pace at which canine cancers progress also means that researchers testing new therapies can get quicker results than they can in human clinical trials. This benefits scientists, dogs and their owners, proponents say.

“Man’s best friend is man’s best biomedical friend,” says Matthew Breen, a geneticist at North Carolina State University. “It’s like having a mobile biosentinel organism that can help inform us about our own medical prospects over the next 25 years.”

Dogs in the vanguard

The biomedical bond between people and dogs is not new; veterinarians have long treated their canine patients with drugs developed for use in people, and doctors have relied on dogs to test therapies and procedures before deploying them in the clinic. Techniques to treat the bone cancer osteosarcoma without amputating the patient’s limb, for example, were first developed in dogs.

Yet today this cross-fertilization is no longer an occasional, sporadic benefit. Researchers are realizing that canine tumors parallel those in people so closely that dogs may be the best reference point for understanding many of our own cancers.

One of the most important similarities between canine and human cancers is that they arise spontaneously, as the end result of a protracted struggle at the cellular level: Over the course of years, cells accumulate genetic damage that disables normal controls on cell division, and emerging tumors evolve ways to evade the immune system. That complexity means there can be many different pathways to cancer that differ from tumor to tumor — and, it turns out, even from cell to cell within a single tumor.

Traditional lab-mouse approaches to studying cancer miss much of that heterogeneity, because the system is more artificial: Researchers typically have to implant tumors into inbred strains of mice whose immune systems have been suppressed.

New genetic research underscores how similar the accumulating damage is in dogs and people. In a yet-to-be-published study, Elinor Karlsson, a genomicist at the UMass Chan Medical School, and her colleagues looked at gene sequences from more than 15,000 human tumors of 32 different types and more than 400 canine tumors of seven different types.

The aim was to identify genetic mutations that were present in the cancers but not in normal cells of the same individual. Such mutations were presumably not inherited but instead were likely to represent genetic damage accumulated over a lifetime, some of which can result in cancer.

That damage looked remarkably similar in the two species, says Karlsson. “Genetically, in terms of what’s driving cancers, it’s basically the same genes in dogs and humans.” Many of the dog tumors, for example, had mutations in genes already known to drive human cancers, such as the tumor suppressor gene PTEN (often mutated in breast and prostate cancers, among others) and the cell-division regulator NRAS (involved in melanoma and other cancers). Notably, mutations often occurred in or near the same locations in the genes in both species, suggesting that they may cause similar dysfunctions.

A similar recent finding came from researchers at FidoCure, a California-based company working on canine cancer. Scientists there are investigating how tumors with specific genetic mutations respond to human therapies. The team reviewed records of 1,108 dogs with cancer, finding that dogs whose tumors carried particular mutations had higher survival rates if they were treated with a human drug specific to that mutation. This implies that the underlying biology of the cancers may be similar in the two species, and if so, researchers ought to be able to work in the other direction, too — using dogs as a test bed to develop new therapies for people.

That has already paid off in a few cancer therapies first developed in dogs that are now in clinical trials or approved for use in people, says Amy LeBlanc, a veterinary oncologist and director of the comparative oncology program at the National Cancer Institute. Examples include immunotherapies for brain cancers; viral therapy that targets lymphoma; and drug therapies against multiple myeloma, lymphoma and brain tumors. Results like FidoCure’s suggest that these therapies could be just the vanguard of many more such drugs.

A faster path to answers

Cancers progress faster in dogs, which means that clinical trials yield results more quickly. For example, tumors often produce an unusual abundance of malformed RNA molecules. Researchers have shown, in mice, that targeting these molecules with a vaccine can delay or prevent the onset of cancers. But testing a preventive vaccine in people wouldn’t yield results for many years, even decades — and funding agencies aren’t likely to support such a long and expensive study based solely on data from mice.

“It would be an enormous leap to go from the mouse studies to some kind of gigantic, 15- or 20-year human cancer prevention study,” says Douglas Thamm, a veterinary oncologist at Colorado State University.

Instead, Thamm and his colleagues tested the vaccine in dogs, which shrinks the timeline to just five years. All the data — from 804 dogs — have now been collected, and the researchers are analyzing them, with an answer on the vaccine’s effectiveness expected by the end of 2025.

Cancer detection techniques, too, can benefit from testing in dogs. Many golden retrievers, for example, will eventually develop a cancer of the blood vessels called hemangiosarcoma. Drugs can usually forestall the cancer’s progression, but many dogs will eventually relapse. Karlsson and her colleagues are studying whether they can detect that relapse in blood samples drawn from affected dogs, a technique known as liquid biopsy.

The technique is still under development, but the hope is that spotting early signs of relapse will allow veterinarians to abandon failing therapies and try something else more quickly, says project coleader Cheryl London, a veterinary medical oncologist and immunologist at Tufts University, who coauthored a 2016 overview of the similarities between dog and human cancers. In contrast, she notes, doctors can’t ethically try experimental treatments on people until standard treatments have clearly failed.

Eventually, liquid biopsy might be used to screen for previously undetected cancers in both dogs and people, Karlsson says. Here, too, golden retrievers are likely to prove invaluable: Because so many of the dogs will eventually develop cancer, researchers don’t need to screen many animals to find enough tumors to study.

Environmental watchdogs

There’s another important way that dogs can benefit the study of cancer — as environmental sentinels. “Dogs live in our environment,” says Breen. “They breathe the same air, they drink the same water. The dog runs across the same herbicide-treated grass that our grandkids run over.” If those exposures increase the risk of cancer in dogs, they’re likely to do so in people, too, since the genomic pathways leading to cancer are so similar.

In people, exposures to various environmental carcinogens might take 25 years to produce full-blown cancers, Breen says. “But the accelerated lifespan of a dog means they may only need to be exposed to it for two or three years.” That makes dogs a quicker way to spot the chemicals that potentially pose the greatest danger to people.

Breen and his colleagues recently put this sentinel idea to the test. They were interested in environmental toxins that might contribute to bladder cancer. The team knew that in dogs, genetic damage that accumulates in cells of the bladder wall often includes a specific mutation called BRAF V595E that is an early marker for bladder cancer. Earlier research had suggested environmental chemicals were linked to the cancer — but which ones?

To find out, the team identified 25 dogs with the BRAF V595E mutation using urine samples. Then they sent out specially designed silicone tags for the dogs. They also sent tags to 76 dogs (matched for breed, sex and age) that lacked the mutation. Each wore the silicone for five days, during which time it absorbed chemicals from the home environment. The owners then returned the tags to the researchers, who extracted and analyzed the chemicals.

The analysis identified 25 chemicals that were more abundant in the dogs with the mutation, and therefore carcinogen candidates. These included flame retardants, plasticizers and combustion byproducts from smoking, fires and vehicle emissions. “They’re the classic kinds of chemicals that are in everybody’s house,” says Breen. An earlier study by Breen and his team noted similar exposure patterns recorded by silicone tags on dogs and silicone wristbands worn by their owners.

A similar approach may help to measure the cancer risk from other environmental exposures, such as the train derailment in East Palestine. To that end, Karlsson and her colleagues recently mailed silicone tags to about 75 dog owners who live near the site. The researchers are now measuring chemicals in the tags and screening blood samples from the dogs to detect genetic changes linked to cancer.

If dogs exposed to chemicals in that train derailment are showing a higher rate of these mutations in their blood, says Karlsson, they and their owners might need to be monitored for an increased risk of cancer.

As researchers continue to study the links between cancers in dogs and people, they often reiterate the benefits that accrue not just to science, but to dog owners and their sick pets. The pets receive highly sophisticated cancer care that their owners might not have access to otherwise, and the owners may get a little more time with their companions. “We’re not experimenting on these animals to their detriment,” says Thamm. “We’re trying to help those individuals.” That, he and others say, is a source of great satisfaction.

This story was produced by Knowable Magazine and reviewed and distributed by Stacker.